America’s Rural Purge

How American TV Sparked the Urban-Rural Divide

In modern media, rural settings are almost universally negative.

On TV, in books and movies, small, rural communities are places to be escaped from (a la Unbreakable Kimmy Schmidt), disrupted (Footloose), or at best, poked fun of for their overwhelming backward-ness (Trial & Error).

We understand the importance of representation in media, and with an election barely behind us that once again laid bare a gaping divide between urban and rural America, the rural portrait we see on televisions, computers, and newspapers impacts the way rural people see themselves, and more importantly, the way they see the country we share.

The Rural Purge

The biggest transition in American televisions that you’ve never heard of.

By the 1970s, TV was only two decades old, and with only the four or five stations grandparents love to bemoan, a significant amount of programming featured rural or western stories, set in lively, happy, thriving communities and places teaming with adventure and possibility.

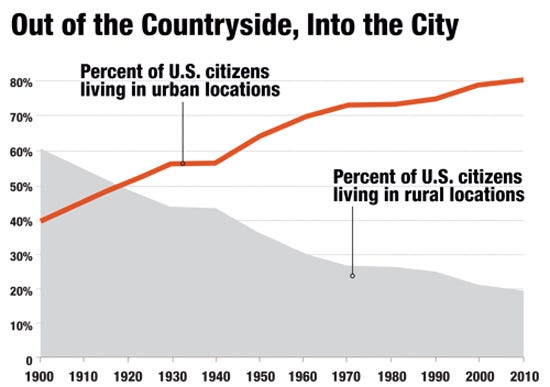

In the 1950s, 8 of the top 30 most watched programs were set in rural communities; Gunsmoke, Bonanza, Lassie, Zorro, The Lone Ranger, Have Gun — Will Travel, The Rifleman, Wagon Wheel (A note on representation by population; 8 of 30, or 27%, was less than the amount of people living in rural places at the time, 36%. Today about 20% of the US population is rural, up slightly this year.) Bonanza, Lassie, Gunsmoke, and The Lone Ranger remained popular into the 60s, and were joined by the likes of The Beverly Hillbillies, Green Acres, The Wild, Wild West, and later in the decade, Hee Haw, Petticoat Junction, Little House on the Prairie, and Mayberry R.F.D.

But by the end of 1975, 31 shows set in rural places (or that appealed primarily to rural audiences), including all of the above, would be cancelled, some at the height of their popularity.

The famous quote at the time was that CBS, the network that ended 16 of the 31 rural shows in a five year window, “cancelled everything with a tree in it.”

Questions lingered about why the change had come, whether it was purely a matter of economics, the bet that young, urbanites would be a better audience for advertisements than the rural crowd, which skewed older. Whether it was about personal biases against the shows by top executives. Or whether it was simply about making a cultural leap forward — introducing characters in the shows that would take these primetime slots (think M*A*S*H, All In the Family, and The Mary Tyler Moore Show) that would face more relevant topics; like racism, the effects of war, and urban issues more head on.

Sure, the transition was rational. There were a limited number of TV channels, and a limited amount of hours in the day to air shows, particularly during prime time. Networks were coming to realize that the programs that aired during those hours not only defined their business, it also defined their viewers. If they wanted to attract younger urbanites with plenty of disposable income and not a lot of time, the prime targets for TV commercials, they were going to be more interested in storylines that reflected their new lives.

So the rural darlings of prime time passed away, and television largely ignored the 1/4 of American’s living in rural places. Norman Rockwell’s pastoral idea was forgotten, and the goings on in small towns became mysterious to everyone else. Unremarkable. Easy to hijack and caricature. And as the country became more and more obsessed with network TV, the 24 hour news cycle, reality shows, and the like, rural America found itself on the outside looking in, without a person or place in the mainstream that looked even remotely familiar.

Why It Matters

The way cultures and groups are portrayed in media has a significant impact not only on the way others perceive them, but on the way that group perceives themselves.

Rural American’s have very few options when looking for the familiar in the media. When they do see rural life, which is portrayed as overwhelming white, uneducated, and poor (not always inaccurately), it’s rarely as a way of life that has value as part of the broader American story.

I think this is at least partly why the idea of corruption and discrimination in media, news media in particular, finds a home among rural populations. When rural voters turn to major TV networks, they don’t find themselves represented and they don’t find their issues talked about. On the contrary, when they see a fellow ruralite or a rural place like their home, it’s almost universally disdained.

If rural people see that the life they know and love is never accurately depicted, why would they believe that anything else they’re seeing is accurate?

The exclusion of the rural story from the American media narrative has been a festering wound for almost 50 years. A way of life lived by an estimated 60 million of our fellow American’s is a mystery to the other 300 million, except those 60 million have an outsized impact on our political process. The only time they really get to have their say on the national stage is on election day.

Why Horror Loves Rural

Realizing a new niche for rural.

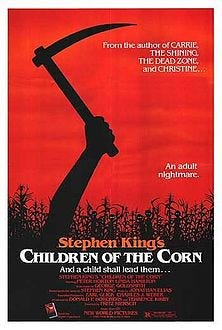

If you were dropped randomly into any rural movie, chances are, it’s a horror film (and if not, it’s Napoleon Dynamite, set in Preston, ID).

What horror movies are picking up in their love of rural settings is the sense that in rural spaces, there is a much broader sense of what’s possible. In horror films, obviously what’s possible is negative — usually involving massive coverups by the whole town or a willingness to put up with terrors, violence, and/or evil that city dwellers would not stand.

But that sense of incredible possibility goes both ways. With a little imagination (and a complete lack of knowledge about rural life), one could imagine a rural place that’s home to an unchecked serial killer. But rural places can also be, for the same reason, some of the most progressive in the country.

Every rural community in America is a kind of petri dish. A place to experiment, where the people who live there can try out new rules and different ways of living, with the potential to make big changes in a short amount of time. Sometimes, maybe most of the time, the experiments will fail. But experimentation is how we move forward. In that way, the rural towns of America are just as likely to be the front lines of our tomorrow, rather than the memories of our yesterday.

Rural communities are the startups of cities.

What it takes to make those experiments — money, of course. Attracting financial infrastructure to America’s heartland is a project being worked on by many, with Steve Case, former CEO of AOL, and his $100 million investment fund and “Rise of the Rest” bus tour leading the way. If we help rural communities get the infrastructure they need (ie, broadband), they could be the next big growth engine for the US economy.

What Now

However annoying it is to page through 600 channels on digital cable or endless options on Netflix or Hulu, the fact that the whole country isn’t confined to 60 TV channels is a good thing. More options means more possibilities for rural programming, and for people to come across characters and settings that challenge their world view. But those options, as with all things, can also serve as echo chambers. With such an overwhelming amount of choice, it’s possible to choose between a huge amount of content, with all of it already agreeing with your world view.

But if we’re serious about bridging the urban-rural divide and about finding a message that resonates and can unite people who seem to live in separate worlds, addressing the way rural America is portrayed in the media has to be part of the strategy.

As an ag and rural issues reporter, I am often asked when farmers are going to turn on Trump, since many of his policies have had outsized impacts on rural economies (see: ag and trade). The answer I hear from rural people day in and day out? Never. Despite all the economic heartache they’re suffering, most farmers I talk to are Trump people. And one of the most common reasons why — because he hears them. He’s spoken at the American Farm Bureau convention and the National FFA Convention (that’s Future Farmers of America, if your Napoleon Dynamite knowledge is rusty). He’s traveled to rural places for roundtables and sends the VP, the Ag Secretary, and others as well. He listens, he speaks to them and stands for them, and he brings the spotlight of the national media with him wherever he goes.

The secret to winning rural America isn’t being conservative or being a republican. It’s about showing people they are not forgotten.

Rural America is looking for someone who doesn’t buy the story that rural America is dying. And the best way to prove it is to show up and see where it lives.

Thanks for reading! Looking forward to your comments. I’ve been interested in figuring out the contours of urban-rural issues for a while now, coming from rural Wyoming to Washington DC, and now reporting on this world back to that one. I’ve had some face time with President, and have spent some time listening to why rural folks like him. Check it out another story on that topic here:

This story is published in Noteworthy, where 10,000+ readers come every day to learn about the people & ideas shaping the products we love.

Follow our publication to see more product & design stories featured by the Journal team.